Simultaneous to his eugenicist activities, Jordan served in academic leadership roles and conducted ichthyological research. He described many of the fish species in North America, Hawai`i, and Japan. Jordan was the founding president of Stanford University, serving in that role from 1891 to 1913. He also was intermittently in office as the president of the California Academy of Sciences between 1896 and 1912. As a curator of ichthyology at the Academy, he collected at least 1,909 type specimens still in our ichthyology collections. Jordan was a member of the Academy from October 5, 1891 when he arrived in California and was elected an honorary life member on January 3, 1898. Through these roles, he exerted power that influenced generations to come.

While Jordan lived and worked at the beginning of the last century, the effects of his ideas reverberate today. The students Jordan hired and taught sometimes went on to be eugenicists themselves. Paul Popenoe, affiliate of the Human Betterment Foundation, co-authored Sterilization for Human Betterment and edited the American Breeders’ Association’s Journal of Heredity. Popenoe and the Human Betterment Foundation also praised the legalization of eugenic sterilization that took place in Nazi Germany. Another of Jordan’s students, Leo Stanley went on to become the medical director of San Quentin State Prison and performed at least 600 sterilizations there, citing Jordan in his motivations for performing eugenic sterilizations in the prison.

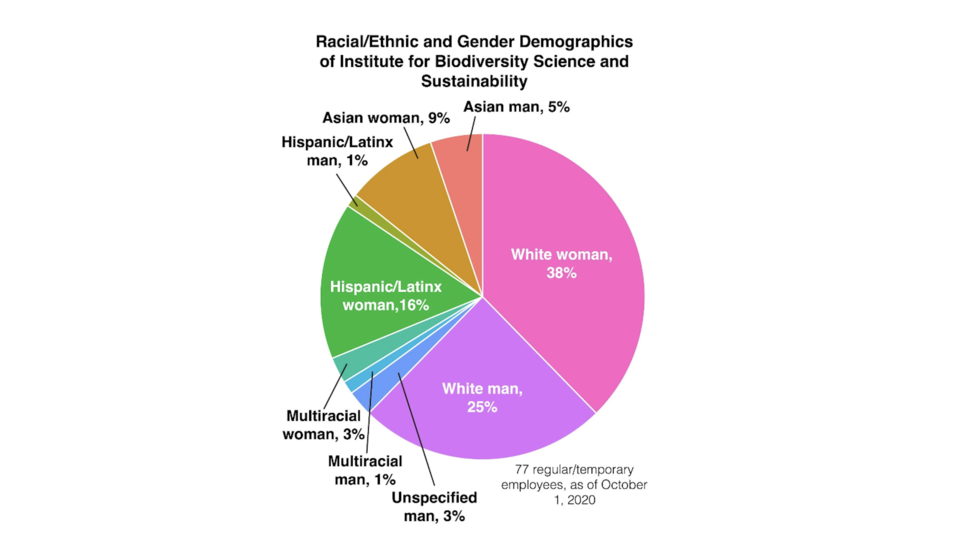

Some of Jordan’s students and contemporaries were not eugenicists but reflected the accepted demographics of scientists at the time—mostly white, mostly men. He taught Barton Warren Evermann, who was an influential executive director of the Academy from 1914 to 1932. Rosa Smith and Carl H. Eigenmann were ichthyologists at the Academy and students of Jordan’s. Frank Mace MacFarland became the director of Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station between 1910 and 1917 and the executive director of the Academy from 1934 to 1938. Jordan taught Alvin Seale, who was the first superintendent of the Steinhart Aquarium. Hence, Jordan’s students went on to be in positions of power, hiring mentees themselves. Starting with a narrow community of people accepted into a profession begets a narrow community who continues on in that profession. Just as with the influence of Cuvier to Agassiz to Jordan, Jordan’s lineage is an example of what Michael Polanyi calls “the apostolic succession of scientists.” While we have made progress in diversifying the Academy’s research staff since Jordan’s time, it is not difficult to see why the demographics of researchers are still majority white (63%).

Jordan was the leader of an academic regime that was based on the closeness of colleagues rather than their academic merits or moral conduct. For instance, Jordan covered up an affair that a colleague, Charles Gilbert, had with a Stanford student because he was friends with Gilbert and did not want to lose Gilbert's academic expertise at the university. Thus, people whom Jordan saw as the best and the brightest (often white men) got a seat at the table and opportunities to advance their careers, while others were left behind, even if they had done work contributing to Jordan’s success as an ichthyologist. Jordan was not one to properly credit his assistants, instead saying, “Of the hundred or more new species of rock-pool fishes lately secured by the writer in Japan, fully two-thirds were obtained by Japanese boys. Equally effective is the ‘muchacho’ on the coasts of Mexico.” The Japanese and Mexican men were not named nor given further opportunities to study ichthyology through an academic lens, but Jordan could not have become such a prolific ichthyologist without them.