By John E. McCosker

Senior Scientist and Chair, Department of Aquatic Biology

Growing up, after the loss of a sweetheart or a baseball, I was comforted by my parents who said, "Oh, don't worry, there are plenty more fish in the sea." They will soon join the passenger pigeon in our museum as most fish stocks are plummeting worldwide.

In North America and Europe, except for an occasional meal of deer, duck, trout, or bass, we have largely given up hunting for food. Most everything we eat, except for wild fish stocks, are cultivated before slaughter. Only from the sea do we still capture our fare by hunting and, as we did on land, we have far exceeded the endowment income and are now consuming precious capital.

More than 70% of the world's fish stocks are overfished, depleted, or worse, extinct as a resource. Even more distressing, is unchallenged research showing that 90% of the large pelagic fishes of the world's oceans—the sharks, billfishes, and tunas—are gone. And the majority of this has occurred since the Second World War. How did this happen? And why wasn't anyone paying attention?

For instance, where have all the roughies gone? Sounds like a Peter, Paul and Mary tune, doesn't it? The orange roughy came and went in a generation. Roughies, previously known by the unappetizing name of slimeheads, are deepwater reef fish that appeared in the New Zealand market in the early 1980s. They are white, flaky, and delicious, and rapidly ascended to the top of fish counters and menus in America and Europe. After a decade of dragging deep trawls over the tops of seamounts, catches plummeted and fishery biologists took a more careful look at roughy life history. They discovered that roughies don't mature until age 30 and can live to 170 years or more. Even more shocking was the discovery that much of the soft coral habitat they occupied, which was 500 years old, was demolished by the bottom trawling used to catch them.

The Chilean sea bass (a.k.a. the Patagonian toothfish), is another slow-growing, tasty, deepwater species with a dim future. Chilean sea bass, with a fishery worth more than 500 million dollars annually, are caught mostly by illegal longline pirates that are also drowning more than 100 thousand albatrosses and other animals each year as bycatch. Whole Foods, Walmart, and other markets have stopped selling it, although it was one of their most popular items, until fishing techniques and fish stocks improve.

So, what can we do? I'm convinced that market forces will succeed in shaping fishing policies and behaviors in ways that governments have been unwilling and unable to control. Some time ago the California Academy of Sciences distributed Catch of the Day wallet-sized cards to guide consumers as to which seafood was sustainable and appropriate to consume. Subsequently the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch cards (available at the Academy) have become the gold standard and are available as a free app. More than 40 million of their cards have been distributed to date and the majority of the general public is familiar with both their cards and the concept of “sustainable seafood.” As proof of possible success, I should note that the Atlantic swordfish, placed in the “bad fish” and “avoid” categories in our original cards, has been elevated to the “good alternative” category because of improvements in their abundance due to better fishery management.

So, are the problems solved? Not by any means, either in America or elsewhere in the world. A significant difficulty remains with the market names of fishes. Learning that Pacific but not Atlantic pollock can be eaten in good conscience, or that shellfish such as the Olympic Oyster or a New Zealand Green Mussel but not a quahog or a geoduck are okay, you will undoubtedly roll your eyes and ask how someone other than an ichthyologist or malacologist can tell the difference? Most can't. And how can one identify a fish fillet, or when a rare fish might be mislabeled to allow its sale or, conversely, common fish flesh might be given a rare, delectable creature's name? What's a buyer to do? Perhaps the best solution is to cultivate a relationship with a fish market or restaurateur that you can trust. The Monterey Bay Aquarium and the Blue Ocean Institute, in partnership with Whole Foods, have designed green, yellow, or red stickers to be placed on wild-caught seafood indicating how sustainable the fishing methods and stocks are.

What then can you consume in good conscience? Generally, sustainable species are small, fast-growing, highly fecund, and early to mature, prime examples being sardines and squid. The least sustainable fisheries are the slow-growing, late-to-mature species that have few young, such as blue whales or loggerhead turtles. And of course the means of capture, from a crabber setting pots (good) to a shrimper dragging a trawl like a highway grader, destroying the ocean floor (ridiculous), affects the outcome and opportunity for future catches.

Between the extremes lie many edible opportunities.

And, as a footnote, you should realize that I am not discussing those marine creatures that should not be eaten because of pollutants such as mercury or parasites that can accumulate in their flesh. (See the Mercury Contamination of Seafood guide.) In particular, children and pregnant women should avoid eating any fish products until you are sure that they are safe.

And, many of you may ask, are aquaculture and mariculture the solution to the overfishing dilemma? Aquaculture has increased so dramatically in the last decade that nearly half of the world's fish products are purchased from farms and hatcheries. Aren't farmed salmon and shrimp abundant, inexpensive, and a way to ease pressure on wild seafood? Unfortunately, no.

At first blush, it would seem that hatchery-reared and farm-raised fish and invertebrates would relieve the pressure on wild stocks, but unfortunately it is often not the case. And for desirable species like salmon and shrimp that reside higher up the food chain, several pounds of fish flesh are required to raise a pound of product, thereby further reducing ocean stocks of other species in the process.

Aquaculture works best for species that consume plants or don't require protein-rich diets, such as carp, catfish, and tilapia, and rearing some shellfish can also purify water by filtering out algae and waste. If the farms are inland and well-contained, there is limited collateral environmental damage due to pollution or the possible escape of such stocks. When done well, fish rearing and processing jobs are created, people are fed, and wild fish find relief: if done badly, we, fish, and the environment are poorer as a result.

The drawbacks to aquaculture are numerous and usually involve: 1) pollution which enters the environment resulting from the pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, and excessive nutrients involved in high density fish farming; 2) the inevitable escape of non-native farmed stocks into freshwater and marine ecosystems; 3) the introduced diseases and genetic dilution of wild stocks which can interbreed with the genetically inferior farmed stocks; 4) the excessive use of freshwater involved with some aquaculture; and the destruction of prime habitats and nurseries such as mangroves (by shrimp farmers) or coastal fjord lands (by Atlantic salmon farmers).

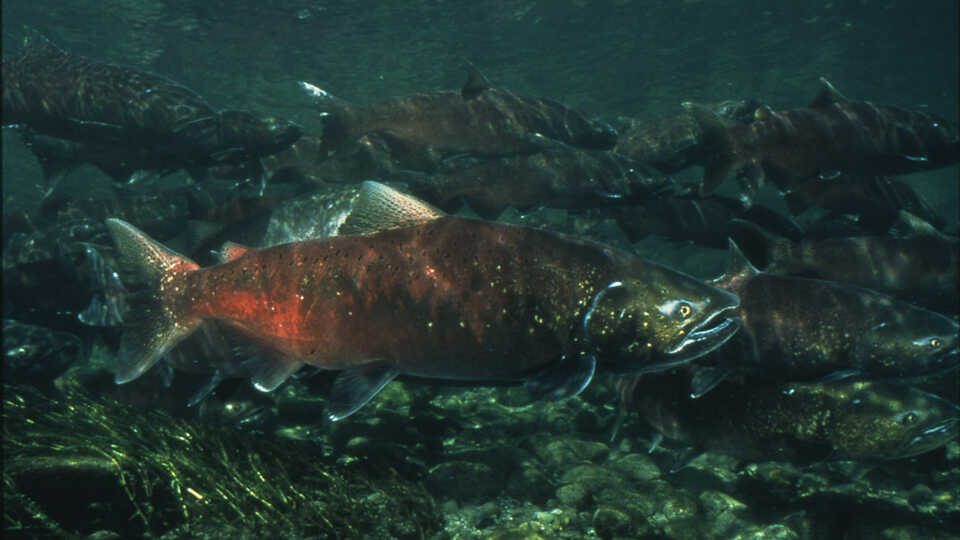

Perhaps the greatest irony concerning salmon is its current abundance—salmon is available in markets and restaurants year-round in most American and European cities, prompting people to ask,"Salmon problem? What salmon problem?"

The current glut is the result of pen-reared Atlantic Salmon, an industry that is currently practiced in British Columbia, Washington state, Norway, France, Maine, and Chile. Some are profiting, but if the balance sheet honestly identified all the current and future costs it is unlikely that buyers would pay the actual cost, which might well be an order of magnitude greater.

Salmon lovers need not despair however, in that many wild Pacific Salmon stocks, particularly those in far-eastern Russia, Alaska, and parts of British Columbia and California are producing sustainable catches. And, unlike much of the farmed salmon, it’s very good for your health.

Now on to shrimp and prawns. They are delicious, and at about $10 billion/year make up the world's largest category of seafood income. About half of shrimp production is caught by boats that drag nets across the bottom and the remainder are farmed in bays and along shorelines, largely in the tropics.

Shrimp trawling has a century-old tradition and is decreasing, whereas shrimp farming is undergoing an explosive gold rush expansion, and both practices contribute to widespread environmental damage. The true costs of markets for "all the shrimp you can eat" in America, Europe, or Japan are being paid by poorer people living in coastal areas in countries like India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Honduras, and Ecuador. Japan and America currently consume one third of the world's shrimp production, but as the economy of China's growing middle class improves an increasing burden is inevitable.

The problem with shrimp rearing is a combination of the devastation of mangroves, the nursery grounds for many fishes and invertebrates, the antibiotic-laden food, the use of pesticides, excessive freshwater usage, and the consumption of vast quantities of fish stocks to feed these carnivorous crustaceans. The lifespan of a shrimp pond rarely exceeds 5 – 10 years. When yields decline, ponds are often abandoned and due to the latent chemical and mineral modifications, are useless for other crops. By the last century's end, more than half of the world's mangrove forest had been destroyed, and half of that was due to shrimp farming, a practice equivalent to the clearcutting of coastal forests. At this time such destruction is accelerating.

An ecologist calculated that the "footprint" of a fish or shrimp farm, its influence on the local environment, can be up to 50 thousand times larger than the farm itself.

The downside of shrimp trawling is less apparent than that of shrimp farming but equally depressing. Imagine, a fleet of 13,000 boats dragging nets that scrape the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, a practice that is 100 years old. Catches of shrimp as well as mackerel, snapper, croaker, and a host of other creatures have steadily declined as a result of the wasteful bycatch clearcutting—more appropriately called "bykill." Worldwide, shrimp fisheries discard 9.5 million metric tons of dead and dying non-shrimp creatures (including many endangered marine turtles) at a ratio often as great as ten pounds of bycatch to one of shrimp.

Now, I will race through the rest of the menu.

All of the following species are overfished and their recovery is often compounded by particular characteristics of their natural history that make them especially vulnerable. Creatures not to consume are the following: most sharks—they are slow, have few young, and are highly vulnerable to overfishing, particularly for shark-fin soup and/or the highly touted but unlikely tumor-inhibiting benefit of their cartilage; beluga caviar—previously fairly well managed, sturgeon are now rapidly disappearing through overfishing since the Soviet breakup; groupers (most species are severely overfished, complicated by the sex-reversal of many species, which results in catches of old fish that are all the same sex, making finding a mate more difficult for their younger partners; north Pacific rockfishes, called red snapper or rock cod, even though they are neither cod nor true snapper—most rockfishes are slow growing and largely overfished; and bluefin tuna, the maguro of sushi—heavily overfished and so rare and valuable that a 593-pound tuna recently sold for $736 thousand!).

So what's left? Several fishery stocks are well managed, sustainable, cause little or no damage to non-target species, and by the way, are quite delicious. On that list are the Pacific albacore, yellowfin or ahi tuna, some wild-caught Pacific salmon stocks, dolphinfish a.k.a. mahi mahi, Pacific halibut, primarily those from Alaska, Pacific sardines, mackerels, squids, farmed oysters, mussels, and clams, and Dungeness crabs. Farm-raised catfish, trout, barramundi, Arctic char, striped bass, tilapia, some sturgeon, and some coho salmon are also okay to eat.

If you want to learn more about sustainable seafood, I recommend that you download the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch report, Turning the Tide: The State of Seafood. And be sure to print and take with you the latest Seafood Watch cards and visit their restaurant program page to learn about restaurants that have taken the pledge. And for your kitchen library you would be wise to search for books such as One Fish, Two fish, Crawfish, Bluefish: The Smithsonian Sustainable Seafood Cookbook, by Carole Baldwin and Julie Mounts (Smithsonian Books, 2003) for delicious recipes for sustainable species.

And what if we don't care? The health of the oceans, already severely jeopardized, is at stake. The fish we like the most are key players in oceanic ecosystems and provide services that we take for granted—until they disappear.

So, as someone who has spent most of his life underwater enjoying fish behavior, and above water enjoying them on my plate, I close by asking you to eat wisely so that your children and theirs may have the same delicious opportunities that we have enjoyed.