In a cooperative effort to publish primary sources, the California Academy of Sciences Archives has completed the digitization of five additional field books as a part of Connecting Content, a National Leadership Grant funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services. Field books record the time, date, location, and circumstances under which a specimen was collected. These detailed notes are used by researchers to retrace the steps of an expedition, understand the methodology behind a collecting trip, and confirm the details of a specific encounter. Connecting Content sought to create contextual links between field books, research specimens, and published literature. In our first round of scanning, we digitized content from field books created by the esteemed researchers Alban Stewart, Rollo Beck, Edward W Gifford, FX Williams, Joseph Hunter, Joseph Slevin, and Washington Henry Oschner during the Academy’s 1905-06 expedition to the Galapagos Islands. These scanned volumes can be found at the Internet Archive and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Rollo Beck photographing a Booby on the Academy's expedition to the Galapagos Islands circa 1905-1906. Beck documented his collecting activities in the field books, which we have recently published on BHL.

C.A.S. Lantern Slide No. 1084. © California Academy of Sciences

Rollo Beck photographing a Booby on the Academy's expedition to the Galapagos Islands circa 1905-1906. Beck documented his collecting activities in the field books, which we have recently published on BHL.

C.A.S. Lantern Slide No. 1084. © California Academy of Sciences

We also photographed a representative selection of bird specimens collected during this expedition, and published them online at

CalPhotos and the

Encyclopedia of Life. Similarly, our partners at the Harvard University Herbaria, The Missouri Botanical Garden, The Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, The New York Botanical Garden, and the Smithsonian Institution digitized

field books and unpublished primary source materials, related specimens, and published texts.

In the interest of broadening our digitized collection to better represent our local holdings, we hired a brave and over-qualified intern called Justin Wasterlain to digitize five field books from former Academy Curator of Botany, John Thomas Howell. He was also tasked with the shared duty of painstakingly teasing out taxonomic names from field book entries on BHL. I asked him to write a bit about his experience:

Since late January, I’ve had the opportunity to work as an intern for the Connecting Content grant project digitizing the field notes of Mr. Howell. As of writing this, we have digitized five volumes spanning from August 1936 until May 1943. Within these books, there are entries for over 5,240 species he collected mostly within the Bay Area and Northern California. Sounds like a lot, right? It’s only a drop in the bucket. The Academy archives hold and additional 64 notebooks of his field notes spanning the collecting years of 1923 through 1984. And this is only one of a multitude of field books created by pioneers of scientific exploration and held by the California Academy of Sciences!

John Howell conducting field work, 1932.

John Howell conducting field work, 1932.

N9288A © California Academy of Sciences

The process of digitizing these books began with scanning them in the Library’s Corsi Digital Lab. As the notebooks were in good condition, not particularly fragile, and created to lay relatively flat, we were able to use a flatbed scanner as opposed to a cradle scanner. Anyone who has made a photocopy will be familiar with that process. But imagine doing so with a delicate, unique historical document. It can be a bit nerve racking at first. Which is good because it forces you to be extremely cautious and precise.

Once scanned, the file is checked to make sure all the basic metadata is appropriate (at this stage, that’s just to say that the file size, name, and type are all what they need to be). If there are any adjustments that need to be made to the image like a closer crop or the like, these were performed in Adobe Photoshop. From there, its final form is stored on the Academy’s servers as a high quality tiff file. After all the books were scanned and saved on the computer, we uploaded the files to Macaw. Macaw is a metadata collection tool developed by the Smithsonian Institution Libraries. For our purposes, it allows us to add page level metadata to the entirety of the books. This includes things like the orientation of the page (verso/recto), the content of the page (cover, blank, text), the date of the work, etc. After page level metadata has been added to the scanned images, Macaw allows us to push the complete digital volume to the Internet Archives and the Biodiversity Heritage Library, where the digitized volumes can be accessed and enjoyed the world over. By uploading the content we have scanned into the Internet Archives and Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), it allows far greater access to the material for researchers and the general public than what the physical object allows. Were you to perform a search for “John Thomas Howell botanical collecting notebook” in BHL, there it is- accessible to anyone with a connection to the internet.

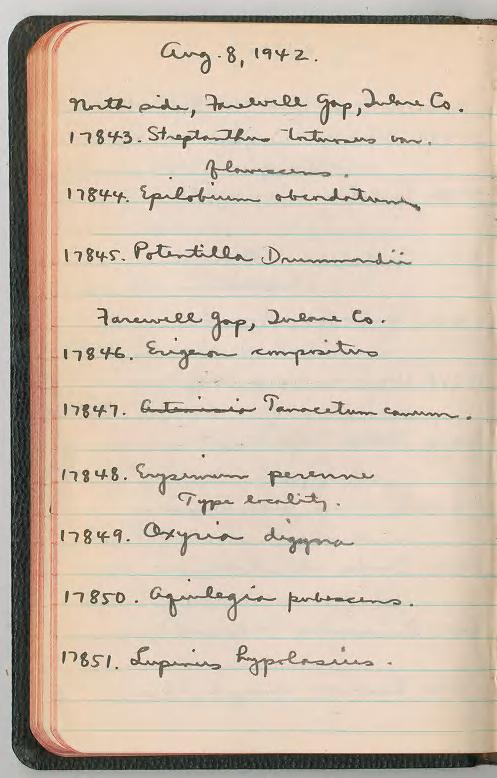

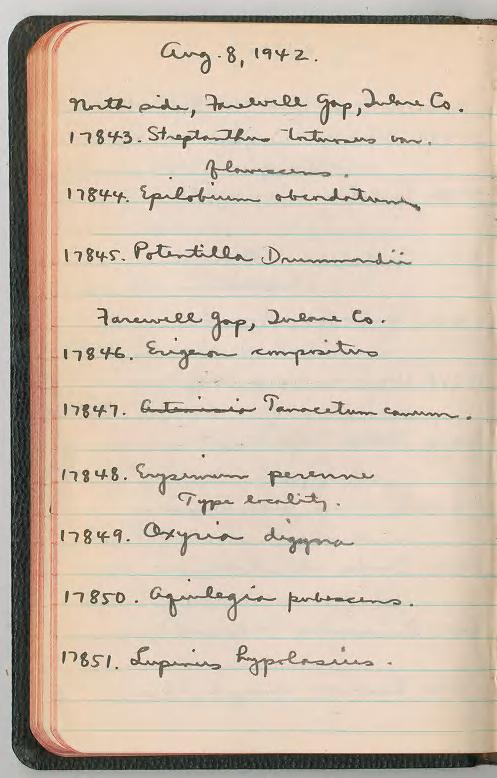

Excerpt from Howell field notebook, volume 37, page 104.

Excerpt from Howell field notebook, volume 37, page 104.

This is only half the process though. In order to make the content searchable, we have labouriously transcribed and verified the scientific names found within the volumes through BHL’s administrative portal. This will make the material searchable and allow for cross referencing the other content within BHL. Moreover, the content is now available for others in the wider science world to use for various projects or applications we don’t even know about yet. They may not either at this point. But by digitizing this material and making it searchable, its use is only limited by imagination. Handwritten volumes are challenging and time consuming to transcribe. Keep in mind these notebooks were handwritten out in the field under less than ideal conditions. Worse yet, a scientist’s cursive handwriting is often unclear; Howell’s penmanship could only be described as “maddeningly squiggly.” Ds look like Hs which look like Ts which are interchangeable with Js. Thankfully there are a number of authoritative taxonomic databases which we check each name against. Ubio, Encyclopedia of Life, and GBIF were constant resources during this process. Particularly uBio which powers the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s taxonomic name search and allows you to type in a few letters of a word and see results that match that beginning. If it comes up blank, you can quickly realize that big swoopy capital Q, is actually a really a sloppy I. This transcription is a slow process of deciphering, verifying, and double checking. -JW

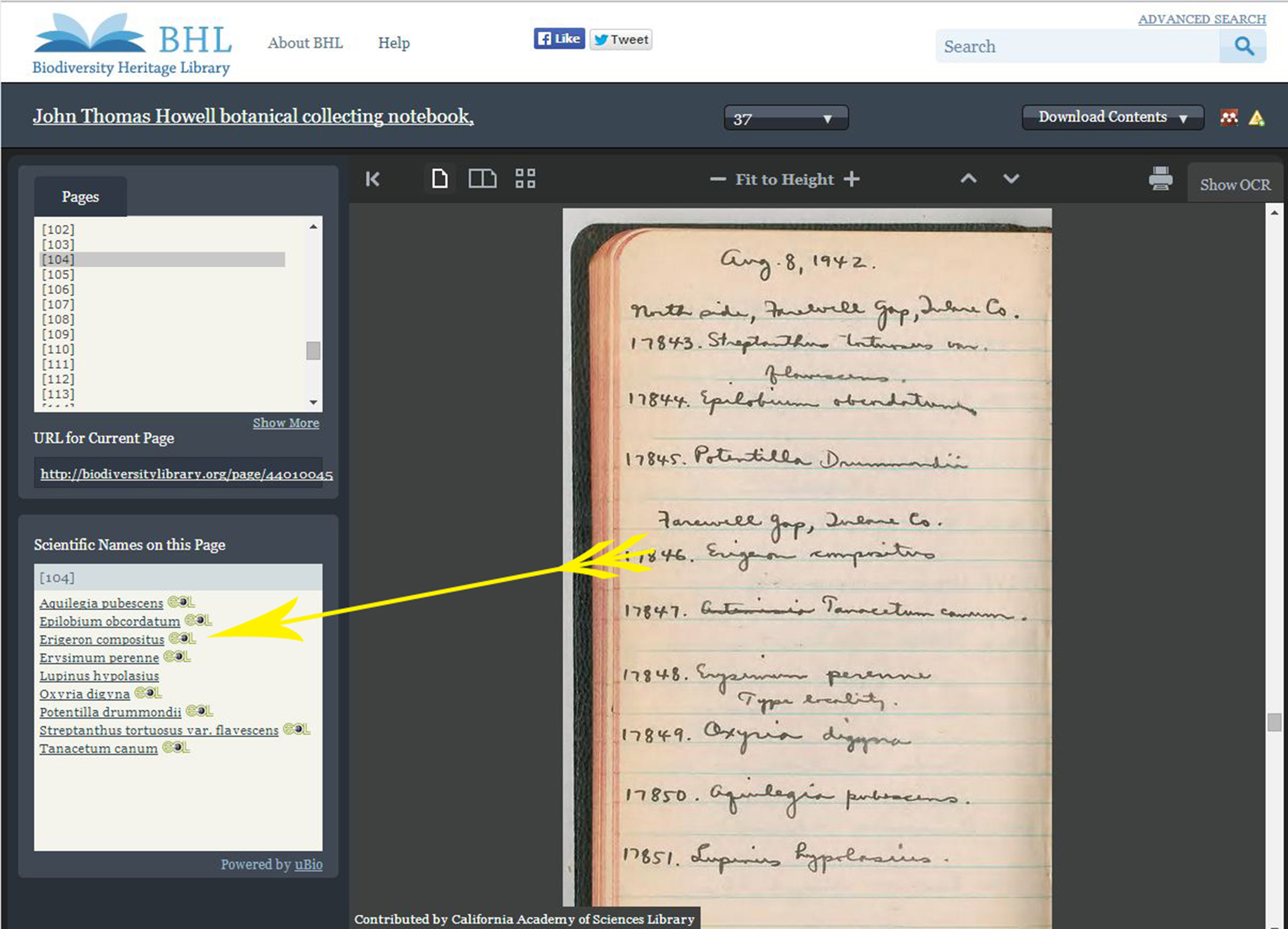

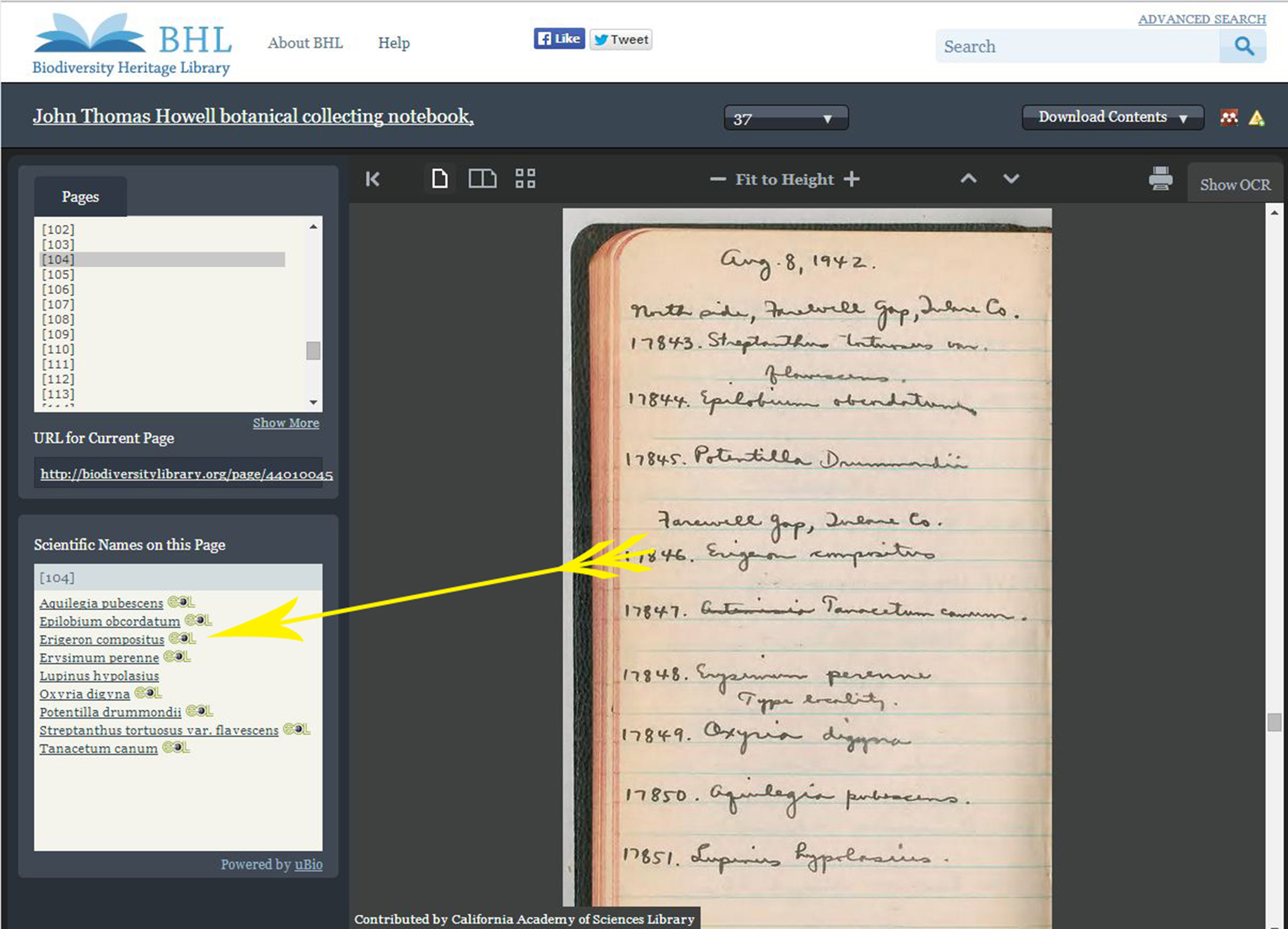

Excerpt from Howell botanical collecting notebook, volume 37, page 104, as viewed on BHL. Every name in the field notes must be transcribed and verified by an actual person!

Excerpt from Howell botanical collecting notebook, volume 37, page 104, as viewed on BHL. Every name in the field notes must be transcribed and verified by an actual person!

We would like to extend a huge thank-you to Justin for diligently spending many hours in front of a computer confirming that he was looking at Erigeron and not Eriogonum or vice versa. I estimate it took us on average at least two minutes per entry and sometimes (although very rarely) as many as ten minutes to pull and verify an individual specimen name from the field books. Given the number of entries in this selection, this means that the process of making these five field books searchable took over 175 hours of labor. This points to the research problem of improving

Optical Character Recognition software and what we might be able to accomplish until technology is able to read and understand the intricacies of human penmanship. Luckily, our peers at the

Smithsonian Transcription Center and

BHL’s Purposeful Gaming project are looking at these problems and working towards viable solutions to help make more field books and primary source materials searchable now and in the future. We hope you’ll join us again in August when we announce what we have built with this test bed of enhanced field notes.. Are you excited that we are making more primary source material available? Let us know in the comments below and we’ll be sure to keep you informed about future contributions.

-Yolanda Bustos, Connecting Content Project Manager

Rollo Beck photographing a Booby on the Academy's expedition to the Galapagos Islands circa 1905-1906. Beck documented his collecting activities in the field books, which we have recently published on BHL.

Rollo Beck photographing a Booby on the Academy's expedition to the Galapagos Islands circa 1905-1906. Beck documented his collecting activities in the field books, which we have recently published on BHL. John Howell conducting field work, 1932.

John Howell conducting field work, 1932.

Excerpt from Howell botanical collecting notebook, volume 37, page 104, as viewed on BHL. Every name in the field notes must be transcribed and verified by an actual person!

Excerpt from Howell botanical collecting notebook, volume 37, page 104, as viewed on BHL. Every name in the field notes must be transcribed and verified by an actual person!