Ever wonder why biologists use weird, hard-to-pronounce names for animal and plant species? Well, it all started with Carl Linnaeus, the famous Swedish 18th Century botanist pictured below.

In the 10th edition of his great work, Systema Naturae (1758), Linnaeus established a system wherein every living species is given but a single scientific name made up of two parts: the Genus (always capitalized) and the species (always lower case and both are always italicized). Among animals, no two species ever have the same name, and this is true among plants, as well. Thus we modern humans are scientifically referred to only as Homo sapiens. In Linnaeus’s day, most scientists wrote in Latin or Greek, thus it was an early tradition to establish these names in those ancient languages. Now, naming of new species is tightly regulated by The International Congress of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN; the botanists have the ICBN). A specific scientific name avoids confusion… here is an example:

The common English name of the critter above is red rattlesnake, or red diamondback rattlesnake; some locals might call it a “red buzzworm!” In French it would be called un serpent á sonnettes rouge; in German: eine rote klapperschlange and if an East African ever saw one, he might call it nyoka sumu nyukundu. See the problem? Not only different base languages, but regional differences in common names serve to muddy the waters. However, the scientific name of this critter is Crotalus ruber, and regardless of their native languages, scientists will always know exactly what species is being discussed. Taxonomists usually try to come up with a name that is descriptive of the species; in this case, Crotalus ruber translates roughly from the Latin as “red bell-ringer,” an obvious reference to its color and the sound made by the rattle.

The Sao Tome shrew: Crocidura thomensis (R. Lima phot, 2009)

Here is another example-- the supposedly endemic shrew we are just beginning to study is called Crocidura thomensis, which means “yellow-tail from Thomas [=São Tomé]”. Probably the first species described in the genus Crocidura had a yellowish tail, although C. thomensis clearly does not.

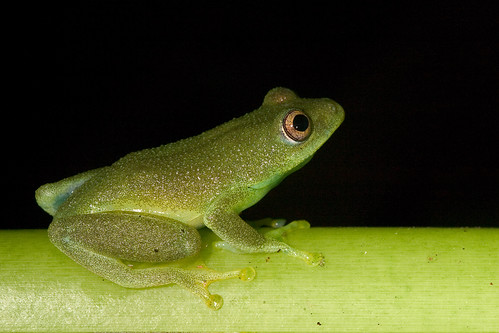

The Oceanic Treefrog, Hyperolius molleri (Weckerphoto GG III)

Scientists may also name species in honor of the person who first collected the specimen; such is the case with the Oceanic treefrog, Hyperolius molleri, found on both São Tomé and Príncipe, M.A.F. Moller was the late 19th Century explorer who first collected the frogs and brought them to Portugal where the species was named in his honor at the University of Coimbra.

Sao Tome puddlefrog, Phrynobatrachus leveleve (Weckerphoto GG III0

Taxonomists have a fair amount of latitude in the choice of words and meanings for scientific names although they are usually Latinized. As an example, Josef Uyeda, Breda Zimkus and I chose Phrynobatrachus leveleve as the new name for one of our own new species of frogs from São Tomé. Phrynobatrachus is an old generic name and actually means “toad-frog;” as to the meaning of leveleve, here is a quote from our paper: The phrase, “leve leve,” generally meaning “easy, easy” or “lightly, lightly” has also been translated by Henrique Pinto da Costa, former Minister of Agriculture, as “calmly, surely.” In our opinion, all three definitions describe the delightful, easy-going demeanor of the citizens of The Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe….it is with the hope that the citizens of this tiny African nation will maintain their ecological heritage and cheerful outlook on life that we name this diminutive endemic anuran. Thus, we named the new species in honor of the attitude of the island citizens.

Illustration by H. Heatwole, 1970

Scientists are also known to inject humor into scientific names, on occasion. The image above is a composite plate from a scientific publication. By way of explanation, many American scientists receive support for their work from our National Science foundation, known universally to us over here as “NSF”. Look at the upper-most image of a frog known scientifically as Physalaemus enesefae… if you are an English speaker, pronounce the species name slowly and you’ll get the humor.

Now for the fun stuff: here is a photo of our latest new species from São Tomé, a mushroom we discovered on the trail up to Lagoa Ameliaduring GG II in 2006. It was formally described just last month in the journal MYCOLOGIA, and Drs Dennis Desjardin and Brian Perry named it after me. It is called Phallus drewesi meaning (literally) Drewes’s penis!

Phallus drewesi Desjardin & Perry 2009 (B. Perry phot. GG III)

As you can see, these fungi are shaped very much like a mammalian penis… they usually grow upright from the forest floor, smell terrible and attract flies! The flies act as vectors disperse the fungus’s spores!

Dr. Brian Perry with a Principe Phallus (RCD phot. GG III)

Members of the genus Phallus can grow quite large. Above is an image of Dr. Brian Perry, one of the describers, holding an example of Phallus atrovolvatus from Príncipe --a rather average sized Phallus.

The author with Phallus drewesi on Sao Tome (Weckerphoto, GG III)

Above is a picture of me holding a couple of examples of Phallus drewesi in 2008, and as you can see, they are quite small! Not only that, but so far as is known P. drewesi is the second smallest species in the world! And, it grows limp! Not proudly erect from the forest floor!

It has been hard for some of my non-scientists to understand what an incredible honor this is. Dennis, Brian and I are good friends and colleagues; in fact, Dennis and I play jazz together as often as we can and serve on the same university faculty.

The author and Dr. Desjardin at Praia Francesa. (Weckerphoto GG III)

It is a great honor because having a species named for you confers a form of immortality. Regardless of what the species is, the scientific name lives on as long as there is science. This is even the case even if decades from now, another scientist learns that this species already has a name – Phallus drewesi lives on in the botanical literature as a synonym. Scientists keep track of all names formally ascribed to a species, whether valid or not. So, yes, it is a wonderful thing to have something named after you, whatever it may be!

Here’s the parting shot:

PARTNERS

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the G. Lindsay Field Research Fund, Hagey Research Venture Fund of the California Academy of Sciences, the Société de Conservation et Développement (SCD) for logistics, ground transportation and lodging, STePUP of Sao Tome http://www.stepup.st/, Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, and Victor Bomfim, Salvador Sousa Pontes and Danilo Bardero of the Ministry of Environment, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe for permission to export specimens for study, and the continued support of Bastien Loloumb of Monte Pico and Faustino Oliviera, Director of the botanical garden at Bom Sucesso. Special thanks for the generosity of private individuals, George G. Breed, Gerry F. Ohrstrom, Timothy M. Muller, Mrs. W. H. V. Brooke and Mr. and Mrs. Michael Murakami for helping make these expeditions possible.