Do you know how many bones a bird has? What about a cat? A shrew?

Honestly, neither do I. It would be rather painstaking to count each bone, especially since it varies among species. All I know is that there are a LOT!

If you’ve been by the Project Lab, you’ve likely seen myself or Codie (or maybe one of our wonderful volunteers) working on preparing study skins. Have you ever wondered what we do when we want to keep the skeletons of these animals?

Depending on the condition of the specimen and the rarity of the species, we can either choose to make both a study skin and what is called a “partial skeleton,” or a full skeleton. Study skins still have a few bones left in them for structure (feet in mammals and skull, wings, legs and feet in birds), so if we want to keep both the skin and a skeleton, the skeleton wouldn’t be complete. If a specimen comes to us too damaged to make a nice skin, we can strip away as much of the meat as possible and keep just the bones. From there, we do one of two things in order to clean off all of the muscle: macerate it or give it to our colony of dermestid beetles.

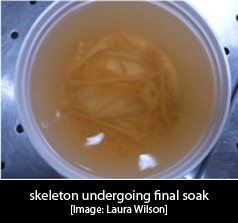

Maceration is the process of rotting the tissue off of the bones in water. Sound disgusting? It absolutely is, but it does the trick! We simply place the body of the animal, with as much muscle removed as possible, in a container filled with warm water and let it soak for a couple of weeks. After a few series of rinses with clean water, we have a beautiful skeleton! You can see a clean skeleton going through its last soak here:

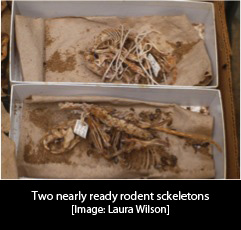

Admittedly, the cooler way to clean these skeletons is with our dermestid beetle colony. These are flesh-eating beetles that, luckily for us, only feed on dead flesh. We don’t have to worry about them munching on us when we add carcasses to their tanks! A few weeks with the beetles and our skeletons come out nice and clean. Here are two rodent skeletons that are almost ready to be taken out from the dermestids:

Both maceration and our beetle colony allow us to prepare skeletons without the use of harsh chemicals that may damage the bone over time. Now “dem bones” are clean and will remain in our collection for hundreds of years!

Laura Wilson

Curatorial Assistant

Department of Ornithology & Mammalogy