Shackleton aficionados seeking a companion piece to Alfred Lansing's classic Endurance will find great satisfaction in Caroline Alexander's book, The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition. Following Lansing by 39 years and the expedition itself by 84, Alexander elaborates further on the crew's personalities, interactions, and ordeals. The text is a product of deep research, contact with families of the expedition members, and access to documents and diaries which, according to the author, were safeguarded for many years. Many of the crew's diary entries are juicy, opinionated, and humorous. They reveal as much about the writers as they do about their colleagues (names are named) and since the majority of the crew kept journals of some kind, their collective writings describe the group dynamic comprehensively.

Shackleton aficionados seeking a companion piece to Alfred Lansing's classic Endurance will find great satisfaction in Caroline Alexander's book, The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition. Following Lansing by 39 years and the expedition itself by 84, Alexander elaborates further on the crew's personalities, interactions, and ordeals. The text is a product of deep research, contact with families of the expedition members, and access to documents and diaries which, according to the author, were safeguarded for many years. Many of the crew's diary entries are juicy, opinionated, and humorous. They reveal as much about the writers as they do about their colleagues (names are named) and since the majority of the crew kept journals of some kind, their collective writings describe the group dynamic comprehensively.  Distinguishing this book are 140 photographs taken by Frank Hurley, the expedition's photo documentarian. Hurley, an Australian, had run away from home at age 13 and worked at a steel mill and dockyards before returning to study at the local technical school and attend science lectures at the University of Sydney. He eventually became a self-taught photographer, setting himself up in the picture-postcard business. Hurley reportedly had an early taste for danger, gaining a reputation for putting himself at risk in order to achieve spectacular images such as situating himself on railroad tracks to capture oncoming trains on film. Led by his adventurousness, at age 25 Hurley signed on as official photographer to Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911-14 which explored the 2000-mile long Antarctic coastline south of Australia. That voyage subsequently brought Hurley to Shackleton’s attention.

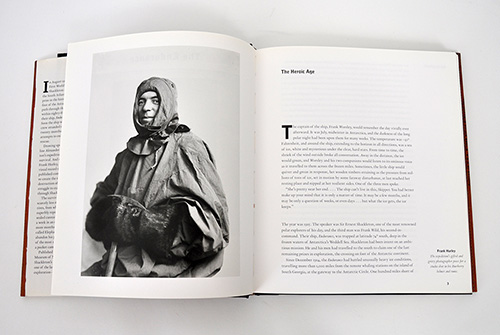

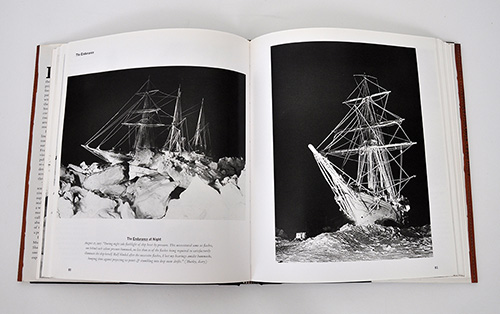

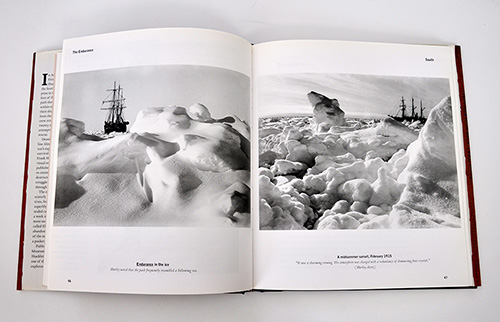

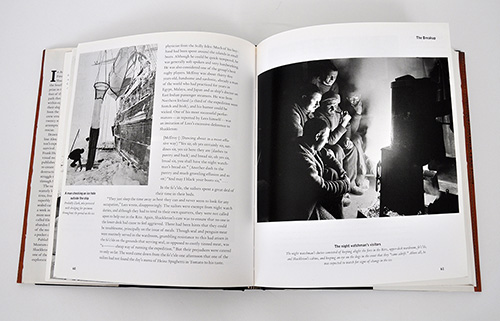

Distinguishing this book are 140 photographs taken by Frank Hurley, the expedition's photo documentarian. Hurley, an Australian, had run away from home at age 13 and worked at a steel mill and dockyards before returning to study at the local technical school and attend science lectures at the University of Sydney. He eventually became a self-taught photographer, setting himself up in the picture-postcard business. Hurley reportedly had an early taste for danger, gaining a reputation for putting himself at risk in order to achieve spectacular images such as situating himself on railroad tracks to capture oncoming trains on film. Led by his adventurousness, at age 25 Hurley signed on as official photographer to Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911-14 which explored the 2000-mile long Antarctic coastline south of Australia. That voyage subsequently brought Hurley to Shackleton’s attention.  Enlisted as Shackleton's photographer in 1914, Hurley advanced his reputation for stopping at nothing to secure a memorable picture. He ventured into darkness, fog and uncertain terrain to get his shots, and scaled the extreme heights of the ship's rigging to capture majestic panoramas. As Lionel Greenstreet, the vessel's First Officer, wrote: "Hurley is a warrior with his camera & would go anywhere or do anything to get a picture." Alexander elaborates on Hurley's dedication to his art: "Once the Endurance became trapped, Hurley turned his camera to both the domestic life of the ship, and to the vision of it improbably suspended in the protean world of the ice. On duty at all hours of the day or night, sometimes arising at midnight to take photographs, he was keenly sensitive to the variegated and ever-changing play of light, continually elated at this spectacle of sky and ice and shadows." Hurley's nighttime images of the doomed Endurance are among his best-known photos. His diary entry of August 27, 1915, describes this undertaking: "During night take flashlight of ship beset by pressure. This necessitated some 20 flashes, one behind each salient pressure hummock, no less than 10 of the flashes being required to satisfactorily illuminate the ship herself. Half blinded after the successive flashes, I lost my bearings amidst hummocks, bumping shins against projecting ice points & stumbling into deep snow drifts."

Enlisted as Shackleton's photographer in 1914, Hurley advanced his reputation for stopping at nothing to secure a memorable picture. He ventured into darkness, fog and uncertain terrain to get his shots, and scaled the extreme heights of the ship's rigging to capture majestic panoramas. As Lionel Greenstreet, the vessel's First Officer, wrote: "Hurley is a warrior with his camera & would go anywhere or do anything to get a picture." Alexander elaborates on Hurley's dedication to his art: "Once the Endurance became trapped, Hurley turned his camera to both the domestic life of the ship, and to the vision of it improbably suspended in the protean world of the ice. On duty at all hours of the day or night, sometimes arising at midnight to take photographs, he was keenly sensitive to the variegated and ever-changing play of light, continually elated at this spectacle of sky and ice and shadows." Hurley's nighttime images of the doomed Endurance are among his best-known photos. His diary entry of August 27, 1915, describes this undertaking: "During night take flashlight of ship beset by pressure. This necessitated some 20 flashes, one behind each salient pressure hummock, no less than 10 of the flashes being required to satisfactorily illuminate the ship herself. Half blinded after the successive flashes, I lost my bearings amidst hummocks, bumping shins against projecting ice points & stumbling into deep snow drifts."  The importance of Hurley's work was not lost on Shackleton. As the Endurance was going under, 'The Boss' saw to it that 120 of the photographer's best images and some motion-picture footage be saved from the sea. Having curated their selection, Shackleton and Hurley then smashed the remaining 400 glass negatives to expel any temptation of taking them along, recognizing that the party’s survival depended on meeting space and weight limitations. Twenty of the rescued plates include Hurley's pioneering images using the briefly popular Paget process of color photography, featured in an earlier Long View post. Obligated to cast off his professional equipment as well, Hurley captured the rest of the expedition on a handheld Vest Pocket Kodak camera and three rolls of film. In testament to his talent, the small-format photos are as fascinating as the larger images and as revealing as diary entries. To see the men's eyes is to connect with them emotionally; to witness their transformation over the course of the expedition is to comprehend their ordeal; to behold their rescue on Elephant Island is to fathom heroism and miraculousness against all odds. The very first time I read Lansing's Endurance, I was unaware of Alexander's book and kept wishing for a thorough photographic reference to navigate by. Alexander provides this much needed pictorial resource, and her text too is an enlightening complement to Lansing's narration. With both books you may, like me, find yourself reading Lansing and Alexander side-by-side, cross-referencing the two for the ultimate Endurance experience.

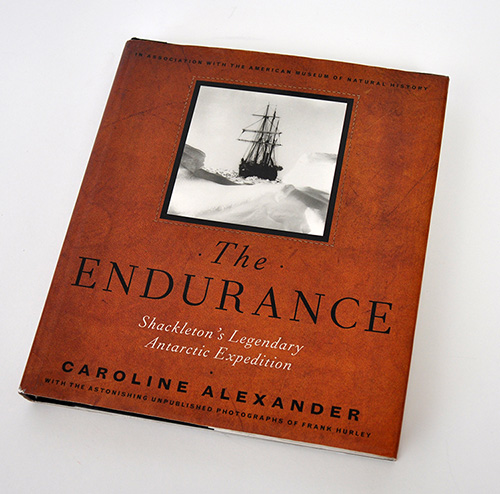

The importance of Hurley's work was not lost on Shackleton. As the Endurance was going under, 'The Boss' saw to it that 120 of the photographer's best images and some motion-picture footage be saved from the sea. Having curated their selection, Shackleton and Hurley then smashed the remaining 400 glass negatives to expel any temptation of taking them along, recognizing that the party’s survival depended on meeting space and weight limitations. Twenty of the rescued plates include Hurley's pioneering images using the briefly popular Paget process of color photography, featured in an earlier Long View post. Obligated to cast off his professional equipment as well, Hurley captured the rest of the expedition on a handheld Vest Pocket Kodak camera and three rolls of film. In testament to his talent, the small-format photos are as fascinating as the larger images and as revealing as diary entries. To see the men's eyes is to connect with them emotionally; to witness their transformation over the course of the expedition is to comprehend their ordeal; to behold their rescue on Elephant Island is to fathom heroism and miraculousness against all odds. The very first time I read Lansing's Endurance, I was unaware of Alexander's book and kept wishing for a thorough photographic reference to navigate by. Alexander provides this much needed pictorial resource, and her text too is an enlightening complement to Lansing's narration. With both books you may, like me, find yourself reading Lansing and Alexander side-by-side, cross-referencing the two for the ultimate Endurance experience.  The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition was first published in 1998 by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, in association with the American Museum of Natural History. The book served as the catalog for the museum's 1999 Shackleton exhibition which showcased Frank Hurley's photos and film footage as well as the legendary James Caird lifeboat.

The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition was first published in 1998 by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, in association with the American Museum of Natural History. The book served as the catalog for the museum's 1999 Shackleton exhibition which showcased Frank Hurley's photos and film footage as well as the legendary James Caird lifeboat.