We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

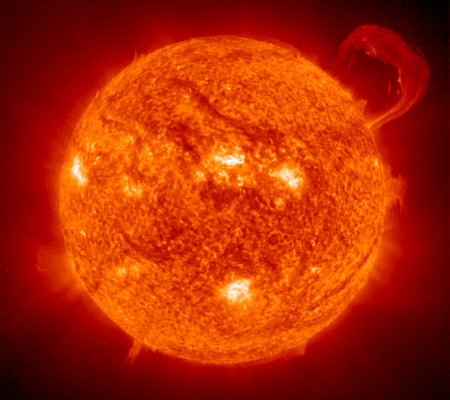

Death by Superflare?

May 17, 2012

by Alyssa Keimach

Solar flares are generated by an abrupt release of magnetic energy around sunspots, a process that Nature News describes quite vividly:

Solar flares occur when magnetic-field loops threading through sunspots get twisted and break, releasing massive amounts of radiation and accelerating charged particles into space.

Although large flares from our own Sun can wreak havoc on satellites and power grids on Earth, it could be worse. Distant stars observed by the Kepler mission are emitting “superflares,” which carry 10 to 10,000 times more energy than average solar flares. If our Sun had these outbursts, they would damage the ozone, kill off species, and cause a change in the amount of sunlight emitted.

Fortunately, superflares are rare. Observing 83,000 Sun-like stars, a team of Japanese researchers, poring over Kepler data, determined that only 148 emitted superflares. The astronomers studied fluctuations in the stars’ overall light.

Could our Sun emit a deadly superflare? No.

Most of the superflare stars rotate quickly, unlike our slow-rotating Sun. ScienceNOW describes why this increases the stakes for superflares:

Most of these feisty stars spin fast, intensifying magnetic fields that spawn spots and flares.

Additionally, most of the superflare-emitting stars are quite young, unlike our middle-aged Sun.

What causes these superflares? It’s a mystery. One theory suggests that hot Jupiters are to blame. These Jupiter-sized planets rotate so close to their parent stars that the two massive objects might interact to supercharge the stellar flares.

Many scientists, including Lucianne Walkowicz of the Kepler team at Princeton University, find the hot Jupiter theory hard to believe. Walkowicz told Nature News:

It seems extremely unlikely that a planet is causing these flares. More likely, it means that even when [stars are rotating slowly], they are occasionally able to store up their magnetic energy and release it in these big flares. It's really a mystery as to how and why that happens.

The study was published earlier this week in the journal Nature.

Alyssa Keimach is an astronomy and astrophysics student at the University of Michigan and volunteers for the Morrison Planetarium.

Image: SOHO/ESA/NASA