Please note: Osher Rainforest will be closed for maintenance Jan. 14–16.

Science News

Enceladus' Jets

August 13, 2013

by Alyssa Keimach

As the key to life on Earth, water has also become the key to looking for life on other worlds…

Water on Earth flows through a cycle that most children learn about in elementary school. Some scientists hope that if we notice a cycle on another planet then it could hint at the existence of liquid water: if we find a cycle, then we may find water, and we may find life. So the idea goes.

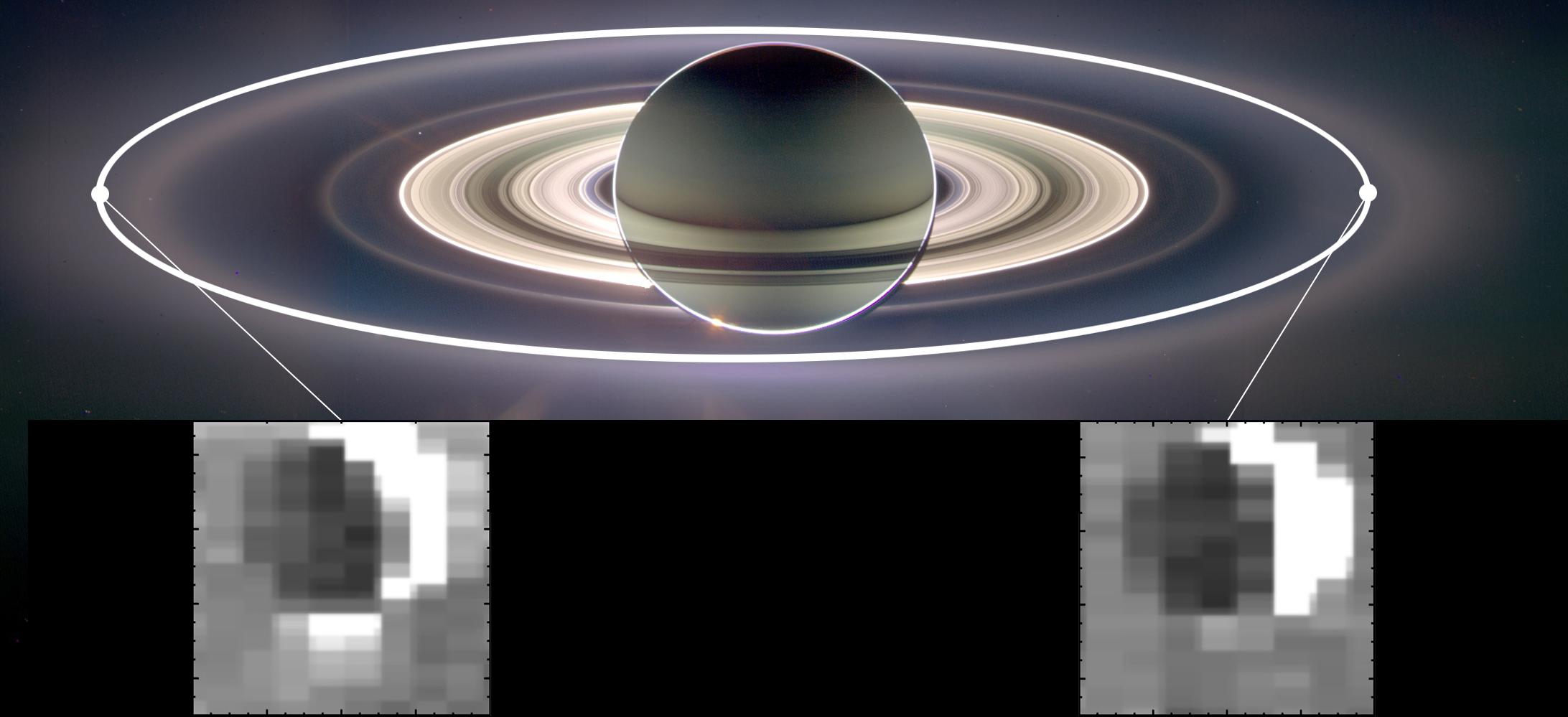

Observations of Saturn’s moon Enceladus reveal geyser jets on its south pole. The jets let out a plume of vapor whose magnitude varies according to predictable times. A paper on the plume cycle, published in the journal Nature, analyzes data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft to study the patterns of ejection from under the ice-covered moon.

“The jets of Enceladus apparently work like adjustable garden hose nozzles,” said Matt Hedman, the paper’s lead author and a Cassini team scientist based at Cornell University. “The nozzles are almost closed when Enceladus is closer to Saturn and are most open when the moon is farthest away.”

The Cassini team observed the jets for the first time in 2005 soon after the spacecraft entered Saturn’s orbit. The team hypothesized that the intensity of the jets would vary over time, but they did not directly observe any variation until they examined over 200 photos taken from the mission.

The images show that the southern plume becomes about four times brighter while Enceladus lies far from Saturn, and dims while it is close. Why? It may have something to do with recent findings about Saturn’s gravitational influence on Enceladus…

The research team believes that Saturn’s gravity squeezes Enceladus and causes the changes in geyser strength. When Enceladus is closer to Saturn, the geyser openings tighten up, allowing less material to escape. When Enceladus relaxes at farther distances, the spray can escape in larger quantities.

“The way the jets react so responsively to changing stresses on Enceladus suggests they have their origins in a large body of liquid water,” said Christophe Sotin, a co-author and Cassini team member. “Liquid water was key to the development of life on Earth, so these discoveries whet the appetite to know whether life exists everywhere water is present.”

So if we follow the water, perhaps we will find life…?

By the way, you can visit Enceladus in Morrison Planetarium! From now through September 5th, check out Fragile Planet at the California Academy of Sciences.

Alyssa Keimach is an astronomy and astrophysics student at the University of Michigan and interns for the Morrison Planetarium.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Cornell/SSI