We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Penguin Count... From Space

April 17, 2012

Emperor penguins live together in large colonies in Antarctica, where temperatures can be as low as –58 degrees Fahrenheit. Quite inhospitable for humans, but it seems to work for the penguins. That’s why scientists are worried about the monochromatic, flightless birds. As temperatures rise and ice melts globally due to climate change, what will happen to the penguins’ habitat?

To learn how to protect a species, researchers must first count the penguins and figure out where they live. Excitingly, they’ve found a new way to do this with the emperor penguins—satellites!

Publishing last week in the open access journal, PLoS ONE, a team of researchers from across the globe has found that satellites can accurately measure penguin populations throughout their remote, often inaccessible homeland.

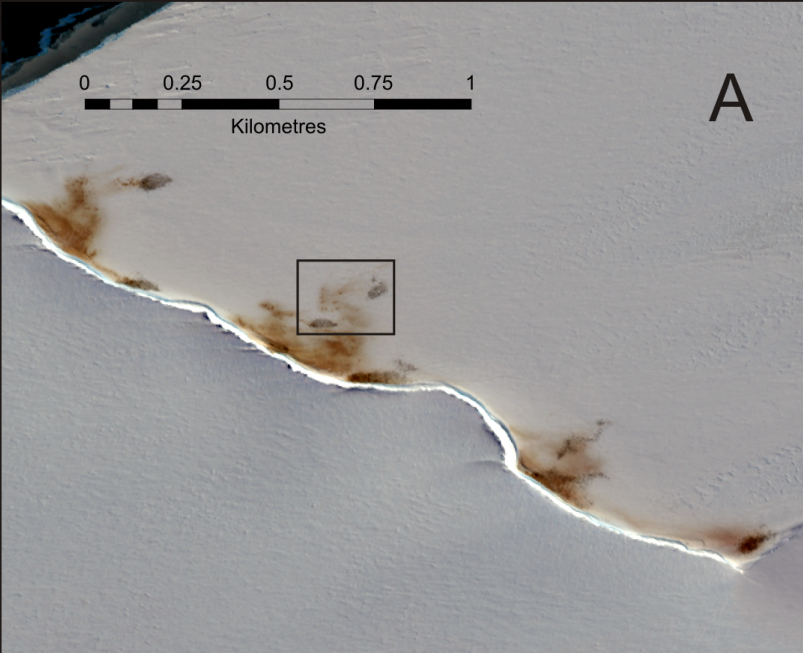

The study reports how the researchers used Very High Resolution (VHR) satellite images to estimate the number of penguins at each colony around the coastline of Antarctica. Using a technique known as pan-sharpening to increase the resolution of the satellite imagery, the science teams could differentiate between birds, ice, shadow, and penguin poo or guano. They then used ground counts and aerial photography to calibrate the analysis.

The satellite data make the researchers optimistic. The researchers found seven colonies in addition to the 44 known emperor penguin groups. And lots more of the iconic birds. “We are delighted to be able to locate and identify such a large number of emperor penguins. We counted 595,000 birds, which is almost double the previous estimates of 270,000–350,000 birds. This is the first comprehensive census of a species taken from space,” says lead-author Peter Fretwell at the British Antarctic Survey.

“The methods we used are an enormous step forward in Antarctic ecology because we can conduct research safely and efficiently with little environmental impact, and determine estimates of an entire penguin population,” adds co-author Michelle LaRue from the University of Minnesota.

“The implications of this study are far-reaching: we now have a cost-effective way to apply our methods to other poorly-understood species in the Antarctic, to strengthen on-going field research, and to provide accurate information for international conservation efforts.”

So far-reaching, in fact, that LaRue will next apply the technique to another species, according to Scientific American.

LaRue is working on similar satellite projects to study Antarctica's Weddell seals, and biologist Heather Lynch of Stony Brook University in New York State is using satellite imaging to study crested and brushtail penguins on the White Continent.

Image: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033751.g001