We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Phytoplankton Under Ice

June 8, 2012

Beneath the Arctic ice—over 12 feet deep in some areas—lies a dark, cold and lifeless sea. Or so we thought.

A team of scientists, led by Stanford’s Kevin Arrigo, broke through some of the Arctic ice last July as part of the NASA ICESCAPE mission and found the complete opposite—abundant life!

“If someone had asked me before the expedition whether we would see under-ice blooms, I would have told them it was impossible,” says Arrigo. “This discovery was a complete surprise.”

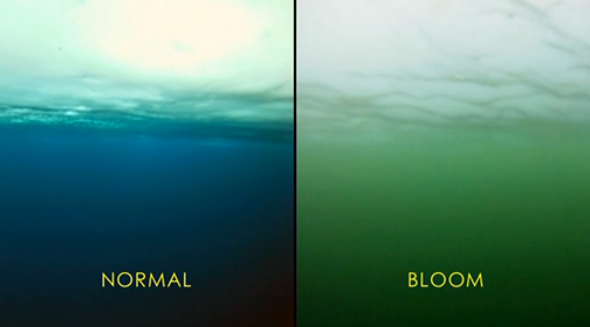

The researchers discovered an abundance of phytoplankton—microscopic life that forms the base of the marine food chain. Phytoplankton require sunlight for photosynthesis, just like plants. And sunlight has a tough time penetrating thick sea ice.

But that thick sea ice is changing. Not only are warmer temperatures thinning the ice, but as the ice melts in summer, it forms pools of water that act like transient skylights and magnifying lenses. These pools focus sunlight through the ice and into the ocean, where currents steer nutrient-rich deep waters up toward the surface. Phytoplankton under the ice evolved to take advantage of this narrow window of light and nutrients.

The phytoplankton displayed extreme activity, doubling in number more than once a day. Blooms in open waters grow at a much slower rate, doubling in two to three days. These growth rates are among the highest ever measured for polar waters. Researchers estimate that phytoplankton production under the ice in parts of the Arctic could be up to 10 times higher than in the nearby open ocean.

The phytoplankton bloom discovered by Arrigo and his colleagues in the Chukchi Sea (just north of Alaska) extends tens of meters deep in spots and about 100 kilometers (62 miles) across.

“At this point we don’t know whether these rich phytoplankton blooms have been happening in the Arctic for a long time and we just haven’t observed them before,” Arrigo says. “These blooms could become more widespread in the future, however, if the Arctic sea ice cover continues to thin.”

The discovery of these previously unknown under-ice blooms could have serious implications for the broader Arctic ecosystem, including migratory species such as whales and birds. Phytoplankton are eaten by small ocean animals, which are eaten by larger fish and ocean animals.

“It could make it harder and harder for migratory species to time their life cycles to be in the Arctic when the bloom is at its peak,” Arrigo says. “If their food supply is coming earlier, they might be missing the boat.”

The research is published this week in Science.

Image: NASA