Science News

Space Friday: Junk, Crash and an Ejection

Space-Junk and Plans to Clean It Up

Astronomers have predicted that a wayward piece of orbiting debris will make an uncontrolled entry into Earth’s atmosphere on November 12, 2015, at 10:20 p.m. PST, falling over the Indian Ocean about 60 miles (100 kilometers) off the coast of Sri Lanka (where it’ll be Friday the 13th). For the time being, the object is temporarily designated WT1190F (or “WTF” by some), and was first detected in 2013, although some pre-discovery images have been found from 2012. Its highly-elliptical, three-week long orbit doesn’t match that of any known artificial satellite and takes it out to nearly twice the distance of the Moon. No one is quite certain what it is, but with an estimated density 1/10 that of water, it’s likely a spent rocket body measuring three to six feet (one to two meters) in diameter and possibly a remnant from a past lunar mission. As it enters the atmosphere, the object is expected to burn up like a meteor, but depending on its actual mass and shape, some portion of it may survive and reach the ground (or, more likely, the water). Astronomers are hoping that they’ll be able to make more detailed observations during the week so they can refine their prediction.

On any clear night, observers in dark locations can usually see several satellites orbiting high overhead—a very small fraction of the roughly 1,300 artificial moons that presently circle the planet. Not just operational satellites, however—there’s also a lot of debris in the form of booster stages, discarded shrouds, bits of insulation, and other space-flotsam. All told, there are an estimated 20,000 human-made objects larger than a softball in orbit, and the number of objects the size of a marble or smaller may exceed 100 million.

It’s getting crowded up there, and spacecraft including the now-retired Space Shuttle and the enormous, football-field-sized International Space Station have been struck by small, millimeter-size bits of debris. Larger objects pose a greater risk, and in the event of a close-approach by a softball-size object moving 17,000 miles (27,000 kilometers) per hour, the massive Space Station must undertake a debris avoidance maneuver to avoid a collision. In a worst case, the astronauts and cosmonauts take shelter in one of the docked Soyuz spacecraft, ready to evacuate if necessary. To deal with the growing hazard, two groups have been planning tests to clean up space junk. JAXA, the Japanese space agency, launched the Space Tethered Autonomous Robotic Satellite (STARS-2) in February 2014. Although this was only a two-month long test to see if the 980-foot (300-meter) long “magnetic net” would unfurl properly and generate power, the device is designed to magnetically attract stray bits of debris and drag the load into the atmosphere, where it would burn up on reentry. If all goes well, the STARS system could begin deployment in 2019.

Meanwhile, three-year old Swiss Space Systems (S3), has announced plans to test what it calls “CleanSpace One“ by 2018. A 66-pound (30-kilogram) robotic module that will rendezvous with one of two defunct target nanosatellites, CleanSpace One will grapple the target with a robotic arm, then—like STARS—perform a controlled de-orbit, incinerating both itself and its load in the atmosphere.

Space-faring countries have been launching an increasing number of objects into orbit around Earth and beyond for more than a half-century—maybe it’s time we started cleaning up after ourselves. –Bing Quock

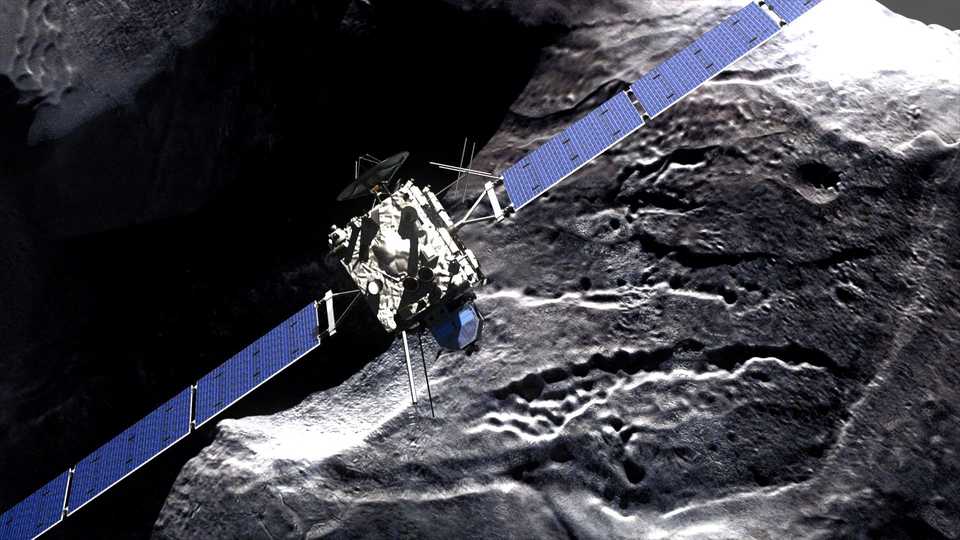

Rosetta's Fate Decided

The fate of ESA’s Rosetta mission was announced this week in Nature—a “gentle” crash landing next September into the icy comet it orbits.

“Funding for the mission runs out in September 2016—and by that time 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko will be well on its way back out into deep space, where the solar-powered orbiter will receive too little sunlight to function,” announced flight director Andrea Accomazzo.

With that date in mind, discussions about the mission’s end have been ongoing for over a year. Initially, the team hoped the spacecraft could land on the comet’s surface and hibernate while 67P carried it through deep space to aphelion and back, reawakening the spacecraft when the comet approached the Sun in another four to five years.

The idea has merit. Rosetta spent much of the first ten years of its mission in hibernation waiting to be activated. There is also precedent landing an orbiter on a rocky body even though it was not designed to do to—NASA’s NEAR Shoemaker mission ended its mission around the asteroid Eros by completing a “soft landing” on the surface and remained functional for a time after. And of course, team members thought it would be fitting to reunite Rosetta with the Philae lander it launched to the comet’s surface a year ago.

However, there are major concerns that the aging spacecraft would not survive the second, long shutdown or if its resources like fuel, power, and funding would last another reawakening. And crash landings have yielded valuable, up close data of other solar system objects before—such as the probe from NASA’s Deep Impact crashing into comet Tempel 1 in 2005, or the Messenger mission’s hard landing on Mercury earlier this year. Bringing Rosetta down for a slower, albeit harder, landing has many benefits. The craft has more powerful sensors on it than Philae does, so a slow descent would allow it to collect more data and better images of the surface.

“The crash landing gives us the best scientific end-of-mission that we can hope for,” says Rosetta project scientist Matt Taylor.

But crashing an orbiter so that it can collect and send useful science on the way down is more complicated than it sounds. For example, the descent must be orchestrated in a way that the crash lands on the comet's Earth-facing side. And its irregular, iconic rubber-duck shape will make the approach to the surface tricky as well. Orbiter navigators and operators are currently working out potential orbits that will bring the spacecraft spiraling closer to the comet until its precise, carefully crafted crash.

Some still hold out hope for a change of heart allowing Rosetta to more peacefully touchdown and hibernate, but either way, until then, Rosetta still has work to do. New announcements such as last week’s discovery of molecular oxygen on the comet remind us that 67P still has much to tell us. –Elise Ricard

Selfish Jupiter?

Could there have been five gas giants in our solar system at the time of its formation four billion years or so ago? The idea that there was one more gas giant planet in addition to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune was first proposed in 2011, when researchers hypothesized that a close encounter with another gas giant (maybe Jupiter or Saturn) caused the fifth planet to be ejected from the Solar System. But how? And by which remaining planet?

A study published this week in the Astrophysical Journal identifies the suspect. “Our evidence points to Jupiter,” says lead author Ryan Cloutier of the University of Toronto.

Planet ejections occur as a result of a close planetary encounter in which one of the objects accelerates so much that it breaks free from the massive gravitational pull of the Sun. Cloutier and his colleagues believed that this type of encounter would have also had an effect on the remaining planet and its moons and their orbits. So they developed computer simulations based on the modern-day trajectories of Callisto and Iapetus, moons orbiting around Jupiter and Saturn respectively. They then estimated the likelihood of each moon residing in its current orbit in the event that its host planet was responsible for ejecting the hypothetical planet—an incident which would have caused significant disturbance to each moon’s original orbit.

“Ultimately, we found that Jupiter is capable of ejecting the fifth giant planet while retaining a moon with the orbit of Callisto,” Cloutier says. “On the other hand, it would have been very difficult for Saturn to do so because Iapetus would have been excessively unsettled, resulting in an orbit that is difficult to reconcile with its current trajectory.” –Molly Michelson