Scientist Spotlight

Terry Gosliner

Terry Gosliner’s lifelong passion for nudibranchs and the natural world has taken him to the depths of the Indo-Pacific Ocean and into classrooms and government offices across the globe, all in an effort to increase protections for biodiversity hotspots and raise awareness about ocean sustainability.

Identify everything

Terry Gosliner grew up in Marin, California, during a time when the landscape was largely rural. He recalls a childhood defined by exploration of the hills and tide pools near his house, and by a never-ending quest for more and more knowledge about the natural world.

In elementary school, Gosliner—already obsessed with field guides—asked his mother, an Academy Member, to order the institution’s quarterly scientific papers.

“I was hungry for knowledge,” Gosliner says. “I wanted to be able to identify everything I encountered in my life and to know what it was.”

Virginia Gosliner sought out nature talks, signed her son up for local seaweed and shoreline walks, and found a used microscope for sale at a UC Berkeley lab. Soon after, a middle-school teacher lent Gosliner the 1963 publication, Animals Without Backbones: An Introduction to the Invertebrates. Armed with that book, his microscope, and a bucket of creek-water that sat on his bedroom desk, Gosliner spent nights and weekends peering through the lens at life forms made visible in droplets of water.

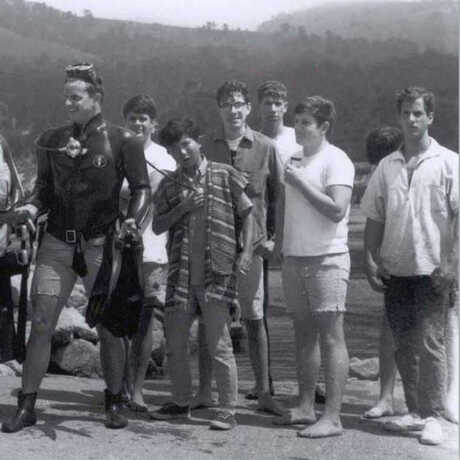

Gosliner’s high-school science teacher, Gordon Chan, was famous for his after-school field trips to places like Point Reyes seashore and Marin’s Civic Center lagoon. One fateful day, Gosliner showed Chan a drawing of a nudibranch (invertebrates also known as sea slugs) and asked to see what they looked like in the wild.

“Once he showed me a living nudibranch,” Gosliner says, “I was hooked. That’s when I really started looking into California nudibranch species. I wanted to find every single one of them.”

Today, Gosliner is one of the world’s foremost authorities on nudibranchs and their relatives, but his first scientific discovery—a species outside its normal geographic range—was made in Chan’s high-school class. Before the end of his senior year, Gosliner had not only collaborated on his first scientific paper about that nudibranch (which was published in the California Malacozoological Society's journal), he’d also discovered his first new species.

Call of the nudibranchs

Nudibranchs are soft-bodied marine mollusks found in oceans across the world, from Antarctica to the tropics, at a wide range of depths. Famous for their often extravagant colors and wildly diverse—and just plain wild—assortment of shapes, they’ve evolved a raft of intriguing defense mechanisms to compensate for their lack of a hard, protective shell.

Some nudibranchs have admirable camouflage skills; others go the opposite way, exhibiting shockingly bright colors and patterns meant to warn predators away. Perhaps their most impressive defense, however, is an arsenal of chemical weapons, many shaped by diet. Nudibranchs that feed on certain sponges, for example, become toxic to predators when they concentrate the sponges’ toxins in their own bodies. Nudibranchs adapted to feed on hydrozoans—like the Portuguese man o’ war—can safely ingest and store their dinner’s stinging cells, eventually moving those cells to the outsides of their own bodies and becoming stingers in their own right.

“This [range of defenses] is what makes the nudibranchs so diversified,” says Gosliner. “It results in their freedom of movement, diversity of form, and the intensely bright coloration they use to advertise against predators. Everything about them just piques the imagination.”

Gosliner estimates he’s discovered between 1,200 and 1,500 new species of nudibranchs (so far) and published more than 150 scientific papers. He’s also authored five books and has “described”—the formal process of scientifically documenting and naming new discoveries—a whopping 296 new species.

And that very first nudibranch discovery—the one made in high school—was actually a joint effort with close friend and classmate Gary Williams, now also a Curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology at the Academy. It took several years for Gosliner and Williams to confirm that their 1967 specimen was, in fact, a new species, but when the two finally published their discovery in 1975, they named it Hallaxa chani—a tribute to their high-school science teacher.

Finding a hotspot

After earning a PhD at the University of New Hampshire, Gosliner headed for the South African Museum in Cape Town, where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet. The waters there were not only considerably warmer, they were also relatively unexplored.

“So few papers had been published on the nudibranchs of South Africa that everything I was finding there was new,” Gosliner recalls. “I thought it was biodiversity heaven. Little did I know.”

In 1982, when Gosliner was hired by the Academy as an assistant curator, “we thought Papua New Guinea was the center of biodiversity,” he says. “It was the only part of the Coral Triangle that had been well studied.”

That all started to change in 1991, while Gosliner was leading a diving team in Papua New Guinea that included a well-traveled underwater photographer.

“He told me, ‘This is really nice, but what I’ve seen in the Philippines is even richer.’ So the next year I went to the Philippines,” Gosliner says, “and he was absolutely right. The biodiversity there was mind-boggling.”

Since that time, Gosliner and the Academy as a whole have conducted more than two decades of exploration, research, and community outreach in the archipelago nation of the Philippines, and those 7,000-plus islands are now recognized as a biodiversity hotspot. The Philippine Coral Reef exhibit that visitors experience today is an extension of that work, mirroring the reef habitats of the Philippines’ Anilao, Batangas, and the Verde Island Passage.

Despite challenging environmental threats to coral reefs and marine life worldwide, the results of Academy work in the Philippines gives Gosliner reason to hope.

“The coral reefs in the Philippines are in better shape today than they were 20 years ago when I began diving there,” he says. “They are surprisingly resilient. Our collaborative efforts in the Philippines show that we can protect these habits. If we can halt damaging activities such as dynamite fishing and pollution run-off, coral reefs and other marine habitats will return to health.”

Redefining research

Everything under the Academy’s roof is a living, breathing reflection of the ongoing work conducted by the Academy’s research division, the Institute for Biodiversity Science and Sustainability. In his three-year stint as IBSS’ Dean of Science and Research Collections and Harry W. and Diana V. Hind Chair, Gosliner oversaw the efforts of more than 100 scientists, collection managers, fellows, and graduate students seeking new knowledge about life’s diversity and the mechanisms of evolutionary change.

“When I first got here,” Gosliner says, “the curators were challenged to become more active as researchers—we made scientific productivity the highest priority.” As he gained more experience, Gosliner sought new ways for the Academy to train and mentor young students and to connect with the community at large. He established a relationship with San Francisco State University, giving Academy curators the opportunity to teach, and focused Academy recruitment on finding scientists eager to engage with the public.

“You can’t just accept discovering science as ‘enough,’” Gosliner says. “We have an obligation to explain its relevance. We need to find more ways to transfer scientific findings to the public so that we can positively impact public policy and conservation management—especially now, when the natural world is changing so rapidly.”

IBSS began a new chapter in 2014, when the Academy’s new Chief of Science and Sustainability, Meg Lowman, succeeded Gosliner as Dean of Science and Research. It’s a move welcomed by Gosliner, freeing him to return his full attention to his own research and lifelong passions: the quest for ever-more knowledge—and nudibranchs—and the promotion of sustainable conservation practices in biodiverse regions like the Philippines.

Department: Invertebrate Zoology and Geology

Title: Senior Curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology

Expeditions: 70

Academy Videos:

"Nature Kid" Meets Nudibranchs

Protecting Unique Ecosystems

Everyday Adventure

Coral Bleaching

Related Content:

"Scientist at Work" blog, The New York Times

"From Beautiful Nudibranchs to Coral Graveyards: Marine Research in the Indian and Pacific Oceans," The Huffington Post

The Wild World of Undersea Worms, Fora TV

Explore IZG projects and expeditions, meet curators and researchers, and browse some of the 2.5 million specimens in the collection.