We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

To Boldly Go Beyond Bars

August 8, 2012

by Nan Sincero

San Quentin State Prison—formidable, ominous, notorious—was built in 1852 by inmates who resided in the first prison in California, The Waban, a ship anchored at Pt. San Quentin in San Francisco Bay. Throughout its 160 year history, San Quentin has housed some of the world’s most famed criminals—Black Bart, Charles Manson, Sirhan Sirhan, and “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez—to name just a few.

Today, San Quentin holds an abundance of California’s most violent criminals (729 of its roughly 5000 incarcerated men are condemned) but the prison is also home to a large general population of inmates and offers a wide variety of educational programs thanks to innovative former warden Jeanne Woodford (1999-2004), who strongly advocated for rehabilitation. Out of the 33 state prisons, San Quentin stands alone in offering such programs, most of which are operated by volunteer organizations, although some are funded by the state, such as the machine shop vocational program.

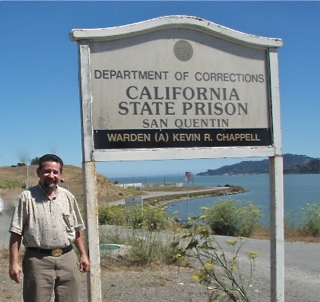

Under the supervision of instructor Richard Saenz (pictured above), the prison’s machine shop, certified by the National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS), has provided metal working and engineering skills to incarcerated men while building crucial machinery parts for the institution for over 13 years. In recent years, the confined shop also completed several outside projects: a magnetic wave machine for the Exploratorium in San Francisco, and elephant seal and sea lion carriers for the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito.

Now the shop finds itself working on the ultimate outside project: building satellite parts for NASA. Poly Picosatellite Orbital Deployers (P-Pods) for CubeSats to be precise—miniaturized satellites used for research by over 150 universities worldwide. Pete Worden, NASA Ames Center Director and co-inventor of CubeSat, got the idea to work with inmates from a conversation with a former guard who stressed the need for prison education programs. Worden has said he also wants to help find jobs for the shop’s well-trained men when they’re released.

The 14 incarcerated men working on P-Pods range in age and years spent behind bars (between 4 and 20). All have either a GED or high school education and are paid between 15 and 35 cents an hour. Four P-Pods have been made so far and although the components are still being inspected, the hope is to one day have them used in testing.

“These parts are technically difficult and there’s no hiding any mistakes”, says Saenz, who has many years of experience working on NASA projects. As a former employee of private firms, he’s built parts for solid rocket boosters, orbital maneuvering systems, and payload assistance modules. And although he enjoyed that work, he prefers his role as instructor at the prison’s machine shop.

“Society needs to learn that people make mistakes and everyone deserves a second chance. Education is key to the future and it’s my main goal”, he said. Throughout the institution, Mr Saenz is a well-respected mentor.

“One of my guys was asked what building satellite parts for NASA meant to him and he boasted, ‘I feel like I’m reaching for the stars... and I’ve never felt like that before!’” Saenz laughed, “And I think that’s pretty damn good”.

Nan Sincero is a naturalist and docent coordinator at the Academy, and a former literacy teacher at San Quentin State Prison.