New exhibit showcases the incredible diversity of prehistoric flying reptiles, how they flew, and surprising details from newly discovered fossils

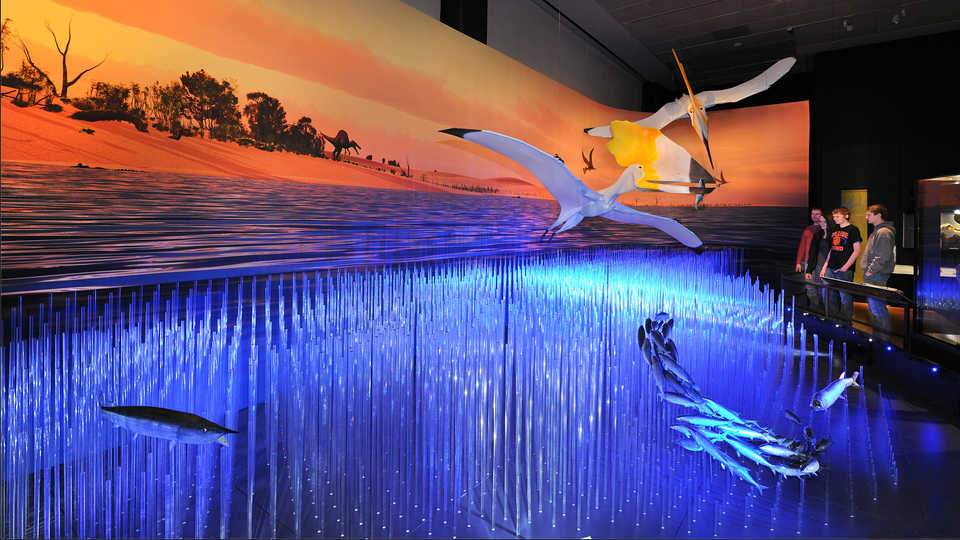

Two Thalassodromeus pterosaurs with impressive 14-foot wingspans swoop down to catch Rhacolepis fish in their toothless jaws in this large diorama showing a detailed re-creation of a dramatic Cretaceous seascape located at the present-day Araripe Basin in northeast Brazil. ©AMNH/R. Mickens

San Francisco (May 5, 2017)—For as long as dinosaurs walked the Earth, flying animals called pterosaurs ruled the skies. They ranged from the size of a sparrow to that of a two-seater plane. Close relatives of dinosaurs, these extraordinary winged reptiles—the first back-boned animals to evolve powered flight, and the only vertebrates to develop this ability besides birds and bats—are the focus of Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs, an intriguing new exhibit opening to the public on Friday, May 19 at the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park.

“We’re thrilled to bring Academy visitors a unique, in-depth look at these fascinating winged reptiles in this new exhibit,” says Scott Moran, Senior Director of Exhibits and Architecture at the Academy. “We hope that through fun interactives, captivating displays of important fossil discoveries, and beautiful, larger-than-life models, visitors will discover the incredible diversity of pterosaurs and the critical role they play in our understanding of the prehistoric world.”

The largest exhibit about these flying reptiles ever mounted in the United States, Pterosaurs highlights the latest research by leading paleontologists around the world and features rare pterosaur fossils and casts from Italy, Germany, China, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Brazil. Life-size models, videos, and interactive displays will immerse visitors in the mechanics of pterosaur flight, including a motion sensor-based interactive that allows you to use your body to “pilot” different species of pterosaurs through virtual prehistoric landscapes.The exhibit features dozens of casts and replicas of fossils from museums around the world, in addition to real fossil specimens, including a spectacular cast fossil that has never before been exhibited outside of Germany and the cast remains of an unknown species of giant pterosaur unearthed in Romania as recently as 2012.

Discovering pterosaur diversity

Despite popular misconceptions, pterosaurs were not dinosaurs, although the two groups are closely related. In fact, these flying reptiles were the first vertebrate animals to evolve powered flight, diversifying into more than 150 species of all shapes and sizes spreading across the planet over a period of 150 million years until they went extinct 66 million years ago. There was amazing variation among pterosaurs, as visitors will discover upon entering the gallery to encounter full-size models of one of the largest and one of the smallest pterosaur species ever found: the colossal Tropeognathus mesembrinus, with a wingspan of more than 25 feet, soaring overhead and the sparrow-size Nemicolopterus crypticus, with a wingspan of 10 inches, displayed nearby. When pterosaurs first appeared more than 220 million years ago, the earliest species were about the size of a modern seagull, but the group evolved into an array of species ranging from pint-size to truly gargantuan, including species that were the largest flying animals ever to have existed. Visitors can also marvel at a full-size model of a 33-foot-wingspan Quetzalcoatlus northropi—the largest pterosaur species known to date.

Unearthing fragile fossils

For paleontologists, pterosaurs present a special challenge: their thin and fragile bones preserve poorly, rendering pterosaur fossils more rare than those of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. Several displays break down the fossilization process to show how the composition of pterosaur bones affects their potential for preservation. Visitors will also find out about conditions that produce particularly valuable fossils and view an exquisitely preserved three-dimensional fossil of Anhanguera santanae. The pterosaur, which died and fell into a lagoon in Brazil 110 million years ago, was buried by fine sediment and the mud formed a hard shell called a nodule around the remains, protecting and preserving the pterosaur for posterity.

Pterosaurs on land, in the air, and over water

Since pterosaur fossils are extremely scarce, and their closest living relatives—crocodiles and birds—are vastly different, even the most elementary questions of how these extinct animals flew, fed, mated, and raised their young are still mysteries. Recent discoveries have provided new clues to their behavior. Like other flying animals, pterosaurs spent part of their lives on the ground. Visitors will see a fossil trackway from Utah that reveals pterosaurs walked on four limbs and may have congregated in flocks. A cast of the first known fossil pterosaur egg, found in China in 2004, shows that pterosaur young were likely primed for flight soon after hatching. An interactive display shows their feeding habits varied widely, ranging from Pteranodon diving for fish, to Jeholopterus chasing insects through the air, to Pterodaustro straining food from water like a modern flamingo.

Focusing on pterosaurs’ unique ability to fly, the exhibit also draws comparisons between pterosaurs and living winged vertebrates: birds and bats. Pterosaurs needed to generate lift just like birds and bats, but all three animal groups evolved the ability to fly independently, developing wings with distinct aerodynamic structures. Other fossils and casts offer additional clues about how pterosaurs lived and behaved. These include a fossil cast of Sordes pilosus, the first species to show that pterosaurs had a fuzzy coat and were probably warm-blooded, just like birds and bats, and even some dinosaurs. A gallery display illustrates the incredible variety of pterosaur crests—from the dagger-shaped blade that juts from the head of Pteranodon longiceps to Tupandactylus imperator’s giant, sail-like extension. Visitors can consider the many theories scientists have about how crests might have been used: for species recognition, sexual selection, heat regulation, steering through the air, or some combination of these functions.

Pterosaurs likely lived in a range of habitats. But pterosaur fossils most easily preserved near water, so almost all species known today lived along a coast. The exhibit features a large diorama showing a re-creation of a dramatic Cretaceous seascape based entirely on fossil evidence and located at the present-day Araripe Basin in northeast Brazil. Two Thalassodromeus pterosaurs with impressive 14-foot wingspans swoop down to catch Rhacolepis fish in their toothless jaws, while a much larger Cladocyclus fish chases a school of Rhacolepis up to the surface. In the background, visitors will see an early crocodile and a spinosaurid dinosaur, which shared a habitat with pterosaurs.

Interactive flight simulator

Several interactive displays help visitors see the world from a pterosaur’s point-of-view. In the Fly Like a Pterosaur interactive, visitors can “pilot” three species of flying pterosaurs over prehistoric landscapes complete with forest, sea, and volcano in a whole-body movement-based display. iPad stations offer visitors the inside scoop on different pterosaur species—Pteranodon, Tupuxuara, Pterodaustro, Jeholopterus, and Dimorphodon—with animations of pterosaurs flying, walking, eating, and displaying crests; multi-layered interactives that allow users to explore pterosaur fossils, behavior, and anatomy; and video clips featuring commentary from scientists and other experts.

Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs is organized by the American Museum of Natural History, New York (www.amnh.org).

Press Contacts

If you are a journalist and would like to receive Academy press releases please contact press@calacademy.org.

Digital Assets

Hi-res and low-res image downloads are available for editorial use. Contact us at press@calacademy.org to request access.